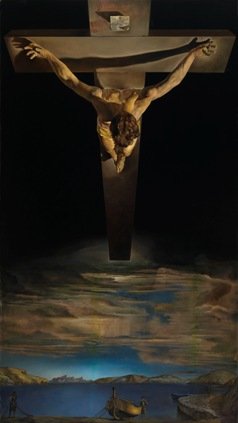

Imitations or reproductions of Dalí’s famous painting are rife in the Catholic world, with an imitation in the office where I work. It takes me back to high school, when I loved Dalí’s artwork. Also, I had just started taking Spanish in school and therefore believed I could read my dad’s battered paperback of Federico Garcia Lorca’s poetry. These are related subjects, I promise, and not simply because I’m discussing Spaniards who, obviously, spoke Spanish.

We had to study a language; it was mandatory in high school. It doesn’t make much sense at that point, however. Learning a second language should have been mandatory from kindergarten onwards. I have an elderly friend at my parish who attended a private American school where they spoke Polish in classes. She still understands and speaks Polish to this day because of her early exposure to it, despite living in an English-only culture. I will never understand the English-only cultural philosophy. It’s not just xenophobic; it’s an example of my least favorite personality trait in individuals, let alone entire cultures: proud ignorance. Generally, I call this the Cult of Stupid. You can spot members because they roll their eyes and complain if you use words with more than two syllables. They think it’s snooty or some such, without recognizing the irony that syllables has three.

Could I actually read the Lorca book? Sure. It had English translations on the right hand-pages. My dad is not a Spanish speaker, after all. I loved learning the pretty vocabulary in the book, as it set me apart from other first-year learners of Spanish. I’ve always had a big vocabulary, and even though I failed pretty badly at English classes in school, I do have the ability to dissect words to determine what they mean. This gives me an even further edge regarding an intellectual grasp of a second language. It’s too bad this process often confuses words for me rather than making them clear. I ran into a funny example this morning. The word equivocarse and its various forms are related to the verb in English to equivocate. By the way, this might not be a commonly used word in English, but it is a common word in Spanish — like so many Latin words that have more than two syllables. In English, this word takes on the meaning of obscuring the truth. To equivocate is either for the purpose of being circumspect or being deceptive. In Spanish, it has the connotation of simply being wrong. I came across a video with the title, Estos policias se metieron con la chica equivocada… It took me a pretty minute, being in an English frame of mind, to realize a correct translation would be “The police messed with the wrong girl…!” My mind wanted it to be deceptive instead of wrong, but it was clear from the context of the video that the girl was innocent, and the police were the deceptive ones. Context is the best guide to learning a language, and so much for my intellectual, dissecting approach. In fact, although this is a bit of a digression, the only way to understand someone speaking Spanish to me is not to be myself, and to listen without focusing on any one word, picking up the sense from the context. If I stop to pick apart words, I have already lost the rest of the conversation. And unlike a language test in school, I’m not going to earn points for translating a few words correctly.

Lorca and Dalí were close friends, albeit I didn’t know this when I was in high school. I only knew I liked reading through my dad’s books, which also included art books featuring Dalí. I’ve loved Spanish ever since I was first introduced to it; that’s all I want to say about that. This post was meant to be about Dalí. But there is a point of overlap with my previous discussion that is much greater than my dad’s bookcases, as it’s clear from reading about Dalí and studying his artwork that he also took the analytical approach to life. He studied the master artists and picked apart the elements in them in order to understand them, and then he spent some time imitating them. Because of this, he’s known as a master of craft. When he created surreal art, he was playing with ideas that intrigued him. For much of his young years, Freudian psychoanalysis was a large part of what intrigued him. He met Freud; Freud didn’t like the surrealists and couldn’t understand why they were fascinated with him. He liked Dalí, though. He liked his genuine fanaticism.

Dalí was also intrigued by the physics of time and space. This in turn intrigued me as a young person. Beauty is timeless, and I will never cease to appreciate landscapes and portraits that capture the personalities inherent to people and places. But playing with ideas perhaps appeals to me even more. Another artist I appreciate for this is M.C. Escher. They both clearly loved playing with what is possible in flat geometric spaces. These two artists have a number of similarities in thinking, to be honest. They both loved the ideas they were representing and loathed politics. Neither wished to be pinned down politically, during a time when being a surrealist artist meant something political. Dalí was actually voted out of the surrealists because he eschewed Marxism and, especially as he grew older, defended Catholicism, eventually returning to his nation’s historical faith (he even had his longtime civil marriage “convalidated” in the church.) Escher was apparently part of a Christian religious order, as well, but he was as quiet about that subject as he was about politics. Dalí enjoyed creating controversy; Escher did not. There are other artists I love because they have an absurdist, intellectual approach — William Hogarth is one that long predates surrealism.

What about Lorca, though? I don’t know; for me, he was simply the first Spanish poet I read. He and Dalí were artistic friends, but Lorca’s approach was different than Dalí’s. He was a gay socialist, fitting neatly into the world of the avant garde. Dalí never fit in, and nor did he want to. He lived to a ripe old age, changing his psychoanalytic approach over the years to bizarre perspectives of Jesus on the cross. Meanwhile, Lorca was assassinated under a fascist regime (though there is some controversy regarding why and by whom).

Like Dalí, ideas are really what drive me forward. Because of that, I will probably never arrive at a place where I’m an artist at storytelling or making music, or a natural with language and communication. But every time I see Dalí’s crosses in my environment, I’m reminded that there are famous artists who don’t approach the world with a traditional artistic temperament. So, perhaps, I still have a fighting chance. By the way, I have tried to subvert the intellectual approach in learning the accordion, but mostly because I don’t have time to give it an extensive study. I want to live in the magic of the instrument and play the songs I love. However, I’ve determined that taking a more intellectual approach will work better for me, having the emotional artistic state of a gnat. So, I’ve stepped back to think through music theory. In Spanish. The problem with my accordion playing is that it’s always been in Spanish. Switching to English would not be a great idea now that I’m used to Do Re Mi Fa Sol La Si, mi acordeon en tono de Fa, and hearing ahora, tocamos la escala de Sibemol en terceras. I know what that is and can play it. If someone switched to now we’ll play the scale of B flat in thirds, I’d probably panic. Intellectuals just do not switch gears with ease, I’m sorry to say. That’s why we’re often labelled fanatics (see Freud on Dalí above). We get obsessed and taken with an idea and must hammer it out to its conclusion.